Zika virus was first identified from the Rhesus monkey in 1947 in the Zika Forest, Uganda. The virus was subsequently isolated from humans 5 years later. Since the 1950s 3 major outbreaks have been reported: 2007 in the Yap islands of Micronesia; 2013 in French Polynesia; and most recently in 2014–2015 in Brazil. Because the symptoms of Zika are similar to several other viruses such as chikungunya and dengue fever, it is likely that cases in other regions have occurred but have not been identified.

Prior to 2007, Zika was not reported outside of Africa and Asia, and since it was first reported in Brazil in May 2015, the virus has swiftly spread across South and Central America and into the Caribbean. During this time, Brazil has seen a concomitant increase in the frequency of neonatal microcephaly. These parallel findings suggested a link between Zika and birth defects—a relationship not previously identified. With the outbreak of Zika infection and its probable link to teratogenicity has come vast media attention. Zika was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the World Health Organization (WHO) in February 2016 and it is predicted that transmission to new countries and territories will continue during the upcoming months to years. In fact, in June 2016, the WHO took the momentous step of recommending that women living in Zika-endemic areas delay child-bearing.

Vector

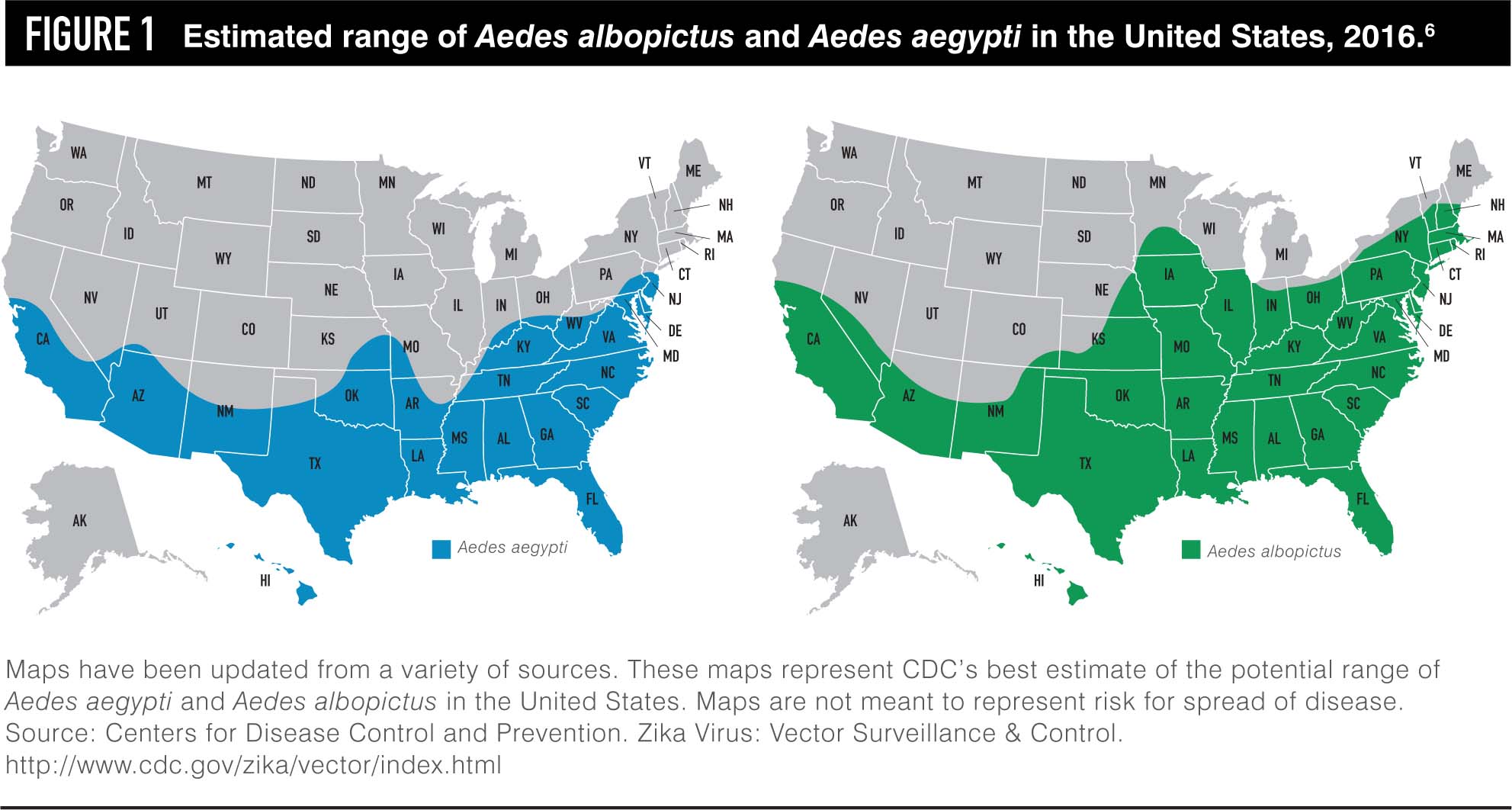

Zika is transmitted to humans via the Aedes species of mosquitoes. These mosquitoes are also responsible for the transmission of dengue fever and chikungunya viruses. The Aedes mosquitoes are unique; unlike other species of mosquitoes, they are aggressive daytime biters. The primary species transmitting Zika to humans is the Aedes aegypti and the secondary species is the Aedes albopictus. The virus is transmitted during a blood meal. Both Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus have been found in the United States, primarily in the southeastern region. Aedes albopictus is the vastly more prevalent species (Figure 1).

Disease features

Zika is a flavivirus, a single-stranded RNA virus. Zika virus is challenging to identify and therefore challenging to study for several reasons.

- First, only 1 in 5 people infected with the virus will become ill.

- Not only are disease symptoms usually mild, they can be identical to many other common mosquito-transmitted viruses. Because mild viral illnesses are ubiquitous in many of the regions affected with Zika, people may never realize they have been infected. In patients who do experience symptoms, these symptoms will occur between 3 and 12 days after being bitten by an infected mosquito and will last between 2 and 7 days. Symptoms include mild fever, maculopapular rash, headache, arthralgias, and myalgias. One distinctive feature of Zika is non-purulent conjunctivitis; while this complaint is also found among patients with dengue fever and chikungunya, its presentation seems to be much more common and severe in Zika cases. Zika has not been shown to cause hemorrhagic fever, and disease requiring hospitalization and/or resulting in death is rare. As in the case of other viral illnesses, once infected, individuals are protected from future infection.

Infection prevention

The most effective methods of disease prevention are to protect against mosquito bites and to reduce opportunities for vector proliferation. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has recommended long-sleeved shirts and long pants in Zika-infected regions both in the daytime and at dusk. Mosquito bed nets are essential if air conditioning or screens are unavailable. The CDC also recommends the application of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-approved repellents to skin and clothing. These products include DEET (N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide) and premethrin. DEET-containing products are recommended for skin application and provide the longest-lasting skin protection. Premethrin should be used on clothing and netting. Products approved by the EPA are not expected to cause adverse health effects and are safe in pregnancy. In fact, reports have suggested it may soon be possible in some states to receive Medicare/Medicaid for DEET products. Finally, vector reduction is essential for disease pre vention. The CDC has advised state and local governments to urge residents to reduce standing water by eliminating old tires, old barrels, and other vessels for standing water. An initiative has begun to treat standing water and wetlands with larvicides such as the bacterial insecticide Bti (Bacillus thurengiensis israeliensis).

Transmission

Although Zika was discovered more than 60 years ago, because adverse pregnancy or birth outcomes have never been previously reported, research into perinatal infection and perinatal transmission is limited and ongoing. Two theories of perinatal transmission exist. The first is transplacental transmission. This theory proposes that virus is transferred directly from the mother to the fetus via the placenta. Once infected, the fetus suffers neural damage as a direct result of the virus. The other theory is one of placental inflammation, which proposes that maternal viral infection creates a placental inflammatory response. This response in turn results in fetal neural damage. The former theory is similar to other documented models of viral transmission and poor outcomes and is the more widely accepted view.

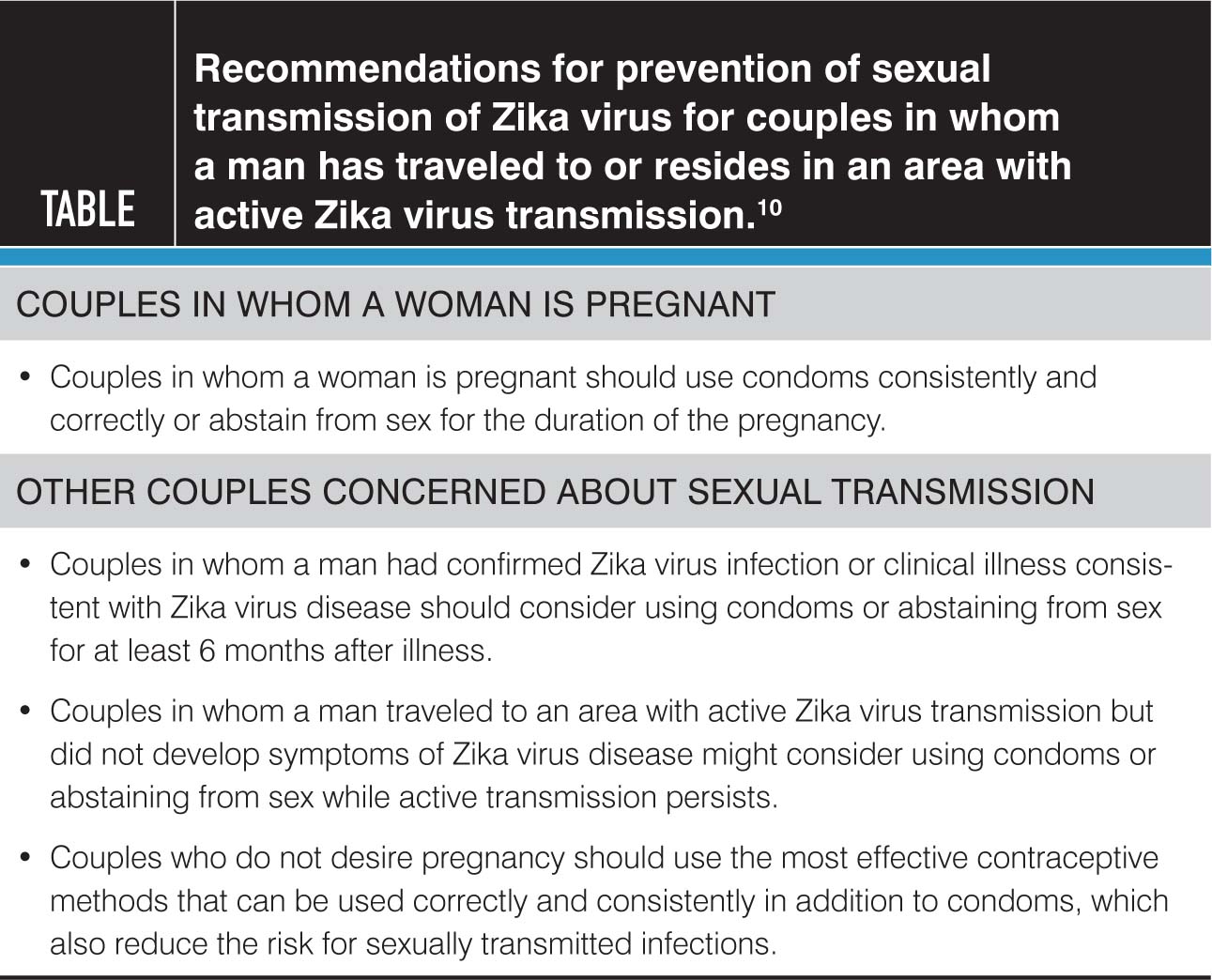

Zika can be sexually transmitted from men to their sexual partners and the possibility of male-to-female sexual transmission with subsequent fetal transmission raises concern. The first documented case of sexual transmission occurred in 2008; this was male-to-female with the sexual contact occurring a few days before the onset of symptoms in the man. With regard to the current outbreak, the first report of sexual transmission was in February 2016. However, as of March 2016, 6 cases of sexual transmission of Zika from men to their sexual partners had been confirmed in the United States. All cases of sexual transmission have been from a man to his sexual partner via vaginal, anal, or oral sex and the sexual contact has occurred before, during, or soon after resolution of symptoms consistent with Zika infection. One recent report out of New York City suggests the first case of female-to-male transmission, however it remains under investigation and it is currently unknown whether asymptomatic men can transmit virus to their sexual partners.

The duration of Zika within the male genitourinary tract is unclear and the process of viral shedding within the genitourinary system is not well understood. As such, Zika testing for the sole purpose of assessing the risk of sexual transmission is not recommended. Because of the risks of transmission from men to women and particularly the risk to the fetus during pregnancy, the CDC has set forth guidelines regarding sexual activity (see bellow)

Two cases of peripartum transmission (ie, transmission at delivery or in the immediate postpartum period) from mother to infant have been reported; both cases resulted in mild disease for the mothers and neonates and no long-term morbidity. While viral particles have been detected in breast milk, breastfeeding has yet to be documented as a mode of transmission. Likewise, infection status after blood transfusion has yet to be reported; however, it is expected, as Zika was found in 2.8% of donors during the 2013 French Polynesian outbreak.

In June 2016, the NEJM published the first report of an affected fetus in the United States. Driggers et al. describe the case of a 33-year-old woman who traveled to Guatemala, Mexico, and Belize during her 11th week of pregnancy. A day after her return to the United States she developed symptoms of a viral infection including rash, mild fever, myalgia, and ocular pain. Her partner had similar symptoms. Serologic testing was positive for both IgM and IgG antibodies against Zika, consistent with Zika infection. Fetal ultrasounds after symptom resolution were negative for intracranial pathology. At 19 weeks, a detailed ultrasound demonstrated brain abnormalities such as bilateral frontal horn enlargement, upward displacement of the third ventricle, absence of the cavum septum pellucidum, and a decrease in head circumference from the 47th to the 24th percentile for gestational age. Fetal MRI confirmed abnormalities of the lateral ventricles, the third ventricle, and the corpus collosum. The patient elected for termination at 21 weeks’ gestation. Postmortem examination of the fetus confirmed the presence of Zika in the amniotic fluid, placenta, fetal brain, muscle, liver, lung, and spleen.

The research regarding perinatal Zika infection, while at times compelling, is limited. And many questions remain. The challenge for patients as well as practitioners is facing the unknown. The true incidence of Zika among pregnant women is unclear, as is the rate of vertical transmission. In turn, among fetuses to whom the virus is transmitted, the rate and range of clinical manifestations cannot be predicted. Indeed it seems there is a delay between maternal exposure, fetal transmission, and ultrasonographically detectable abnormalities, but this time course is not well understood. The case by Driggers et al. demonstrates that fetal abnormalities may not be seen for up to 9 weeks after maternal exposure.

Finally, and perhaps most distressing to expectant mothers, is the unknown prognosis for infants born with Zika infection. Using data from the current outbreak in Bahia as well the previous outbreaks in Micronesia and French Polynesia as models, Johansson and others estimate the risk of microcephaly among infants of mothers infected by Zika to be between 0.9% and 13%. While this estimate is concerning, it must be considered with caution as it is based on modeling and limited retrospective data. Likewise, microcephaly is only one of several potentially adverse outcomes. It is well established that infants with severe microcephaly from other causes will experience a range of neurologic sequelae, but it is unclear if this is true for all cases of Zika-related microcephaly. Neurologic problems can range from intellectual disability to sensory deficits to seizures; they can be mild, severe, or life-threatening. Long-term outcomes are not at all clear and will not be for years to come.

Countries where pregnant women are advised not to travel:

- American Samoa

- Argentina

- Aruba

- Bahamas

- Barbados

- Belize

- Bolivia

- Bonaire

- Brazil

- Cape Verde

- Caribbean

- Chile

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Curacao

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- El Salvador

- French Guiana

- Guadeloupe

- Guatemala

- Haiti

- Honduras

- Jamaica

- Martinique

- Mexico

- Nicaragua

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Puerto Rico

- Samoa

- Saint Martin

- Suriname

- Tonga

- U.S. Virgin Islands

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

Recent Comments